Connecting the Earth Simulator supercomputer to SINET

At the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), the Earth Simulator (one of the world’s fastest supercomputers) is being used in various research and development projects. To get an outline of JAMSTEC’s work and the role played by SINET, we interviewed Jun Naoi and Satoru Okura, sub-leaders of the information systems department at JAMSTEC’s Earth Simulator Center, and Mikio Horiuchi, the group’s assistant technical supervisor.

(Date of interview: March 15, 2010

Perhaps you could start by telling us about the work carried out at JAMSTEC as a whole.

Naoi: JAMSTEC is a Japanese organization that performs multi-disciplinary research into marine science and technology. Our aims are to understand the Earth with a particular focus on marine systems, and to contribute to issues such as protecting the global environment, coping with natural disasters, and securing natural resources. Specific research areas include climate change phenomena such as global warming, the dynamics of the Earth’s interior and natural disasters such as massive trench earthquakes and tsunamis, and organisms that inhabit extreme environments such as deep underwater and deep underground. We are also developing core technologies to support these studies. For example, we have developed and operated various ships, submergence vehicles and remotely operated vehicles such as the CHIKYU deep sea drilling vessel, the MIRAI oceanographic research vessel, the SHINKAI 6500 manned research submersible, and the KAIKO 7000II remotely operated vehicle.

And you’ve opened research centers throughout Japan, haven’t you?

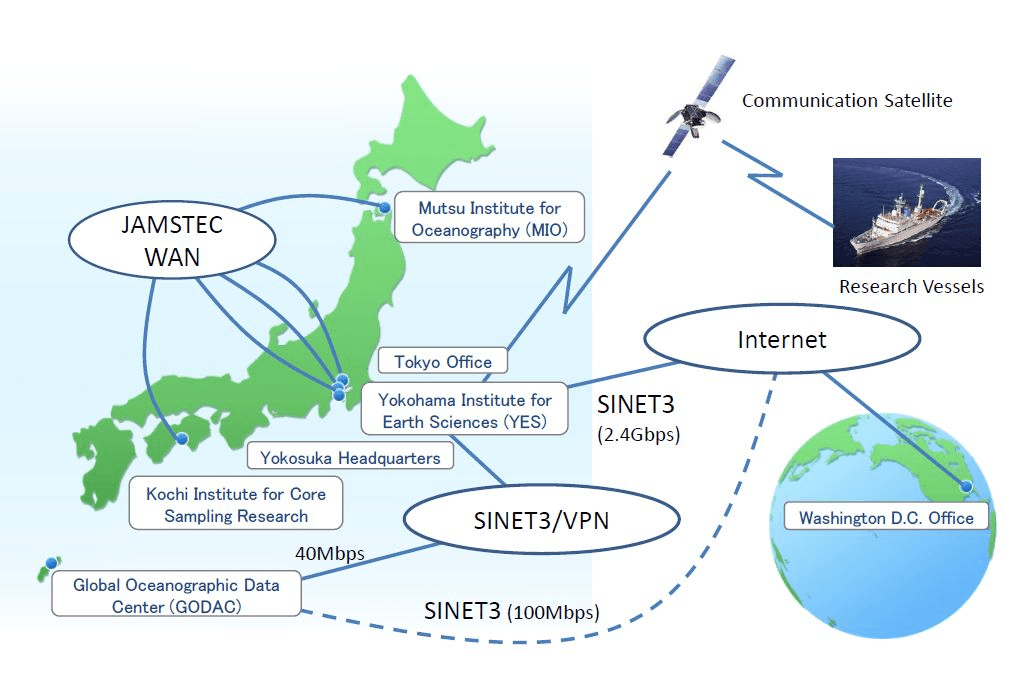

Naoi: Yes, that’s right. In addition to our headquarters in Yokosuka, there’s the Mutsu Institute for Oceanography (MIO) in Aomori, the Kochi Institute for Core Sampling Research in Kochi, the Global Oceanographic Data Center (GODAC) in Okinawa, and offices in Tokyo and Washington, D.C. And here at the Yokohama Institute for Earth Sciences (YES), we not only operate a key center for simulation studies, but we are also responsible for administering JAMSTEC’s IT infrastructure. The YES is home to the Earth Simulator and various business systems, and at the information systems department it is our job to develop and operate these systems.

How is your network environment set up?

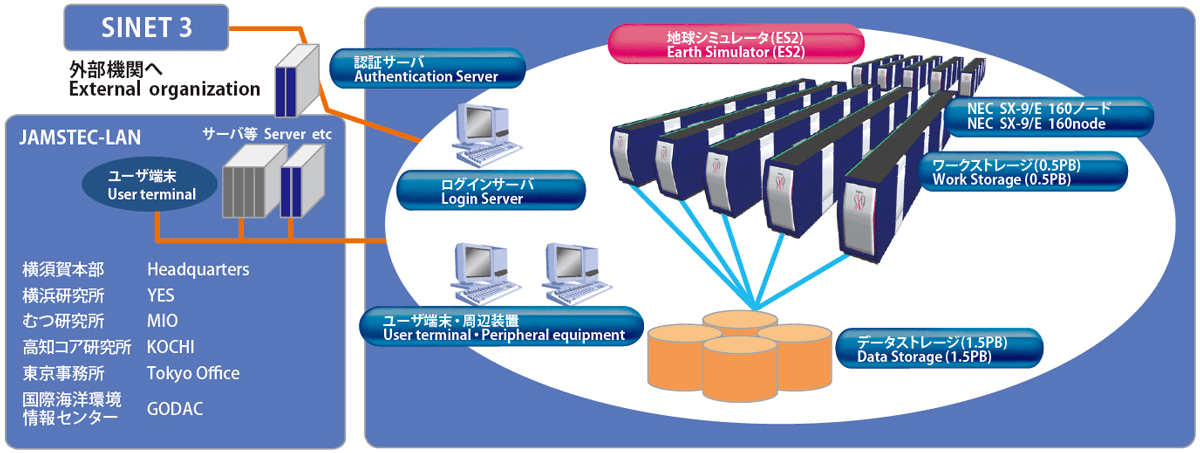

Horiuchi: We are connected to the other centers by a broadband WAN service, and to outside organizations and research laboratories by a SINET3 network. Today, the network plays a vital role in supporting research and day-to-day business operations. We have to be very careful to keep these systems running smoothly in order to avoid outages caused by problems such as equipment failure.

JAMSTEC also has computers that provide external services such as the Earth Simulator, and the amount of data handled by these services has been growing year on year. As a result, the demand for higher network speeds becomes larger every year. In February 2010, we switched over the connection to GODAC from a wideband WAN service to a SINET3 L2-VPN network.

What were your reasons for making this change?

Horiuchi: We wanted to be able to make effective use of large amounts of multimedia data. At GODAC, valuable content such as underwater video footage obtained by submergence vehicles is converted into digital content and made available to the general public via the Internet. The original data is stored at YES, so we need a network that is capable of transmitting large amounts of video data to Okinawa at high speed. The previous environment had a bandwidth of just 10 Mbps, but the switch-over to SINET made it possible to achieve 40 Mbps. We hope to keep bumping up the network speed in the future, because this sort of high-speed network environment is basically an essential requirement for the enrichment of multimedia-based services.

JAMSTEC is of course well known for the Earth Simulator.

Can you tell us briefly what this supercomputer is used for?

Okura: The Earth Simulator was originally developed in the late 1990s to run climate calculations — specifically, a General Circulation Model of the atmosphere — and for this purpose it needed to be capable of operating a thousand times faster than other supercomputers of its time. When operations began in March 2002, it achieved the highest score in tests using the LINPACK benchmark, which is a well-known standard for measuring the performance of supercomputers. Having proved itself to be the world’s fastest computer, it attracted a lot of attention from around the world. This first Earth Simulator was used for research over the next seven years, but eventually it became necessary to update both the environmental and operational aspects of the system. So in March 2009 we replaced it with the current second-generation Earth Simulator (ES2). The ES2 Earth Simulator is configured from 160 SX-9/E nodes with a peak performance of 131 TFLOPS, which at the time made it the fastest computer in Japan and one of the fastest in the world.

How is the ES2 being operated now?

Okura: The Earth Simulator computer resources can be broadly divided into three categories: proposed research projects, contract research projects, and JAMSTEC research projects. The proposed research projects category invites applications from researchers of earth science and other academic fields, and resources are granted to advanced and original research projects. In the 2009–2010 fiscal year, it was used for 16 earth science projects, and 9 projects from other fields. The contract research projects category accepts projects that use the Earth Simulator based on commissioned research or grants by public organizations such as the central government. These include the Innovation Program of Climate Change Projection for the 21st Century. The Earth Simulator is also used for research projects organized by JAMSTEC, international and domestic collaboration projects and the execution of urgent jobs in the event of natural disasters. The overall percentage allocation of computer resources consists of 40% for the publicly accessible framework, and 30% for each of the special projects and organization strategy frameworks. By January 2010, 113 organizations and 569 individual researchers had registered for these frameworks.

I heard that the Earth Simulator is also available for use by private companies for research and product development.

Okura: A single research project can generate several hundred terabytes of data, so we currently have 1.5 petabytes of disk space available for users. As you might expect, it’s not that easy for users to transfer such large amounts of data to their own universities or research organizations. These days, most users tend to access the results of their simulation calculations over the network. If networks continue to evolve in the future, then the way users access their data might change too. So we hope to achieve a lot with SINET.

Finally, what are your hopes for the future?

Naoi: Apart from the plans I mentioned earlier, JAMSTEC is also working with Tokyo University’s Earthquake Research Institute (ERI) on the construction of a network for seismology studies, and is working on allowing ships at sea to connect to the Yokohama Institute for Earth Sciences via the JAXA satellite. As for the information systems department, we hope to provide a stable foundation for this advanced research by expanding the capabilities of our IT infrastructure. At the same time, we hope to upgrade to a faster SINET4 network so we can support studies that take advantage of newer network technology.